Advertisement

Supported by

Doctor’s Death After Covid Vaccine Is Being Investigated

A Florida physician developed an unusual blood disorder shortly after he received the Pfizer vaccine. It is not yet known if the shot is linked to the illness.

Denise Grady and

Health authorities are investigating the case of a Florida doctor who died from an unusually severe blood disorder 16 days after receiving the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine.

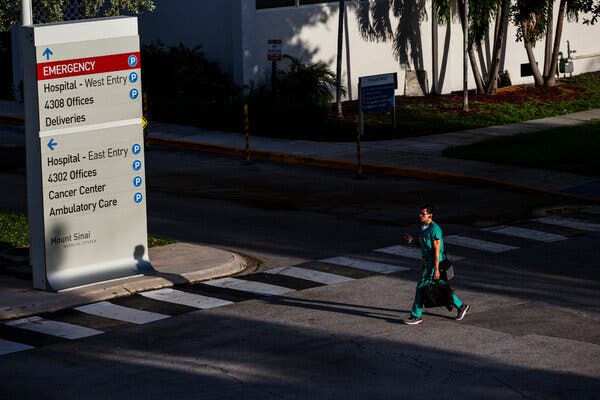

Dr. Gregory Michael, a 56-year-old obstetrician and gynecologist in Miami Beach, received the vaccine at Mount Sinai Medical Center on Dec. 18 and died 16 days later from a brain hemorrhage, his wife, Heidi Neckelmann, wrote in a Facebook post.

Shortly after receiving the vaccine, Dr. Michael developed an extremely serious form of a condition known as acute immune thrombocytopenia, which prevented his blood from clotting properly.

In a statement, Pfizer, the maker of the vaccine, said it was “actively investigating” the case, “but we don’t believe at this time that there is any direct connection to the vaccine.”

“There have been no related safety signals identified in our clinical trials, the post-marketing experience thus far,” or with the technology used to make the vaccine, the company said. “Our immediate thoughts are with the bereaved family.”

About nine million people in the United States have received at least one shot of either the Pfizer or Moderna coronavirus vaccine, the two authorized in the United States. So far, serious problems reported were 29 cases of anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction. None were reported as fatal. Many people have had other side effects like sore arms, fatigue, headache or fever, which are usually transient.

Local and federal agencies are investigating Dr. Michael’s death. Several experts said the case was highly unusual but could have been a severe reaction to the vaccine.

The Florida Department of Health referred Dr. Michael’s death to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for investigation. Kristen Nordlund, a C.D.C. spokeswoman, said in a statement that the agency would “evaluate the situation as more information becomes available and provide timely updates on what is known and any necessary actions.”

The Miami-Dade County medical examiner’s office is still investigating Dr. Michael’s death and has not yet completed an autopsy report or identified a cause of death, Darren J. Caprara, a spokesman, said.

Mount Sinai Medical Center declined to comment, citing patient privacy laws.

According to Ms. Neckelmann, three days after her husband got the vaccine, he developed tiny reddish spots, or petechiae, caused by bleeding under the skin of his hands and feet. Recognizing the spots as a danger sign, he went to the emergency room. A blood test showed the level of his platelets, a blood component essential for clotting, to be at zero, she wrote, and he was admitted into the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Michael had “absolutely no medical issues” and no underlying conditions, Ms. Neckelmann, who declined to be interviewed by phone as she made funeral preparations, said in a text message to The New York Times. “Never had any reaction to any medication nor vaccines.” Her husband, she added, was a healthy, active person who did not smoke or take any medication.

“He was an avid deep sea fisherman and mostly a family man,” she said. “He never got Covid because he used an N95 mask from the beginning of the pandemic. He was adamant in protecting his family and patients.”

Covid-19 Vaccines ›

Answers to Your Vaccine Questions

While the exact order of vaccine recipients may vary by state, most will likely put medical workers and residents of long-term care facilities first. If you want to understand how this decision is getting made, this article will help.

Life will return to normal only when society as a whole gains enough protection against the coronavirus. Once countries authorize a vaccine, they’ll only be able to vaccinate a few percent of their citizens at most in the first couple months. The unvaccinated majority will still remain vulnerable to getting infected. A growing number of coronavirus vaccines are showing robust protection against becoming sick. But it’s also possible for people to spread the virus without even knowing they’re infected because they experience only mild symptoms or none at all. Scientists don’t yet know if the vaccines also block the transmission of the coronavirus. So for the time being, even vaccinated people will need to wear masks, avoid indoor crowds, and so on. Once enough people get vaccinated, it will become very difficult for the coronavirus to find vulnerable people to infect. Depending on how quickly we as a society achieve that goal, life might start approaching something like normal by the fall 2021.

Yes, but not forever. The two vaccines that will potentially get authorized this month clearly protect people from getting sick with Covid-19. But the clinical trials that delivered these results were not designed to determine whether vaccinated people could still spread the coronavirus without developing symptoms. That remains a possibility. We know that people who are naturally infected by the coronavirus can spread it while they’re not experiencing any cough or other symptoms. Researchers will be intensely studying this question as the vaccines roll out. In the meantime, even vaccinated people will need to think of themselves as possible spreaders.

The Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine is delivered as a shot in the arm, like other typical vaccines. The injection won’t be any different from ones you’ve gotten before. Tens of thousands of people have already received the vaccines, and none of them have reported any serious health problems. But some of them have felt short-lived discomfort, including aches and flu-like symptoms that typically last a day. It’s possible that people may need to plan to take a day off work or school after the second shot. While these experiences aren’t pleasant, they are a good sign: they are the result of your own immune system encountering the vaccine and mounting a potent response that will provide long-lasting immunity.

No. The vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer use a genetic molecule to prime the immune system. That molecule, known as mRNA, is eventually destroyed by the body. The mRNA is packaged in an oily bubble that can fuse to a cell, allowing the molecule to slip in. The cell uses the mRNA to make proteins from the coronavirus, which can stimulate the immune system. At any moment, each of our cells may contain hundreds of thousands of mRNA molecules, which they produce in order to make proteins of their own. Once those proteins are made, our cells then shred the mRNA with special enzymes. The mRNA molecules our cells make can only survive a matter of minutes. The mRNA in vaccines is engineered to withstand the cell's enzymes a bit longer, so that the cells can make extra virus proteins and prompt a stronger immune response. But the mRNA can only last for a few days at most before they are destroyed.

He also believed in the promise of the vaccine, she wrote on Facebook.

For two weeks, doctors tried to raise Dr. Michael’s platelet count, and “experts from all over the country were involved in his care,” she wrote on Facebook.

“He was conscious and energetic through the whole process, but two days before a last-resort surgery, he got a hemorrhagic stroke caused by the lack of platelets that took his life in a matter of minutes,” she wrote.

The planned surgery would have removed Dr. Michael’s spleen, an operation that can sometimes help treat the clotting disorder.

Ms. Neckelmann said she told her husband’s story to make people aware of the vaccine’s possible “side effects,” and “that it is not good for everyone, and in this case destroyed a beautiful life, a perfect family, and has affected so many people in the community.”

Dr. Jerry L. Spivak, an expert on blood disorders at Johns Hopkins University, who was not involved in Dr. Michael’s care, said that based on Ms. Neckelmann’s description, “I think it is a medical certainty that the vaccine was related.”

“This is going to be very rare,” said Dr. Spivak, an emeritus professor of medicine. But he added, “It happened and it could happen again.”

Even so, he said, it should not stop people from being vaccinated.

The condition Dr. Michael developed, acute immune thrombocytopenia, occurs when the immune system attacks a patient’s own platelets, or attacks the cells in the bone marrow that makes platelets. Covid itself can cause the condition in some patients.

A long list of medicines, including quinine and certain antibiotics, can also cause the disorder in some people. Dr. Spivak described the reactions as “idiosyncratic,” meaning they strike certain individuals without rhyme or reason, possibly based on unknown genetic traits, and there is no way to predict if someone is susceptible.

“If you vaccinate enough people, things will happen,” he said.

Vaccines stimulate the immune system, and in theory could, in rare cases, cause it to mistakenly identify some of a patient’s own cells as enemy invaders that should be destroyed.

Dr. Spivak said several things made the vaccine the mostly likely suspect in Dr. Michael’s case. The disorder came on quickly after the shot, and was so severe that it made his platelet count “rocket” down — a pattern like that in some cases brought on by drugs such as quinine. In addition, Dr. Michael was healthy and young, compared with most people who develop chronic forms of the ailment from other causes. Finally, most patients — 70 percent — are women. A sudden case in a man, especially a relatively young, healthy one, suggests a recent trigger.

Dr. Paul Offit, an expert in vaccines and infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said that the measles vaccine and measles itself have been known to cause this same clotting problem, but it is usually transient and not serious. It occurs in about one of every 25,000 measles shots, in both children and adults, he said.

Regarding Dr. Michael’s case, Dr. Offit said: “I don’t know what this is. We’ll keep our eyes open and see if it happens to anybody else.” He added, “Right now we’re guessing. It’s an association in time, but not necessarily a causal association.”

Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University, said that although the platelet disorder had been linked to certain drugs, its connection to vaccines was “a big question mark.”

He noted that millions of vaccinations of many types are given each year, and clusters of this platelet disorder do not occur.

Dr. Spivak said that there were multiple therapies for immune thrombocytopenia, and that knowing more about Dr. Michael’s case might help doctors devise better treatment plans in case the disorder occurs in other people after they are vaccinated.

Alain Delaquérière contributed to this article.

Covid-19 Vaccines ›

Words to Know About Vaccines

Confused by the all technical terms used to describe how vaccines work and are investigated? Let us help:

- Adverse event: A health problem that crops up in volunteers in a clinical trial of a vaccine or a drug. An adverse event isn’t always caused by the treatment tested in the trial.

- Antibody: A protein produced by the immune system that can attach to a pathogen such as the coronavirus and stop it from infecting cells.

- Approval, licensure and emergency use authorization: Drugs, vaccines and medical devices cannot be sold in the United States without gaining approval from the Food and Drug Administration, also known as licensure. After a company submits the results of clinical trials to the F.D.A. for consideration, the agency decides whether the product is safe and effective, a process that generally takes many months. If the country is facing an emergency — like a pandemic — a company may apply instead for an emergency use authorization, which can be granted considerably faster.

- Background rate: How often a health problem, known as an adverse event, arises in the general population. To determine if a vaccine or a drug is safe, researchers compare the rate of adverse events in a trial to the background rate.

- Efficacy: The benefit that a vaccine provides compared to a placebo, as measured in a clinical trial. To test a coronavirus vaccine, for instance, researchers compare how many people in the vaccinated and placebo groups get Covid-19. Effectiveness, by contrast, is the benefit that a vaccine or a drug provides out in the real world. A vaccine's effectiveness may turn out to be lower or higher than its efficacy.

- Phase 1, 2, and 3 trials: Clinical trials typically take place in three stages. Phase 1 trials usually involve a few dozen people and are designed to observe whether a vaccine or drug is safe. Phase 2 trials, involving hundreds of people, allow researchers to try out different doses and gather more measurements about the vaccine’s effects on the immune system. Phase 3 trials, involving thousands or tens of thousands of volunteers, determine the safety and efficacy of the vaccine or drug by waiting to see how many people are protected from the disease it’s designed to fight.

- Placebo: A substance that has no therapeutic effect, often used in a clinical trial. To see if a vaccine can prevent Covid-19, for example, researchers may inject the vaccine into half of their volunteers, while the other half get a placebo of salt water. They can then compare how many people in each group get infected.

- Post-market surveillance: The monitoring that takes place after a vaccine or drug has been approved and is regularly prescribed by doctors. This surveillance typically confirms that the treatment is safe. On rare occasions, it detects side effects in certain groups of people that were missed during clinical trials.

- Preclinical research: Studies that take place before the start of a clinical trial, typically involving experiments where a treatment is tested on cells or in animals.

- Viral vector vaccines: A type of vaccine that uses a harmless virus to chauffeur immune-system-stimulating ingredients into the human body. Viral vectors are used in several experimental Covid-19 vaccines, including those developed by AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson. Both of these companies are using a common cold virus called an adenovirus as their vector. The adenovirus carries coronavirus genes.

- Trial protocol: A series of procedures to be carried out during a clinical trial.

Advertisement