The comeback queen of rock 'n' roll

SHOW BUSINESS

Brian D. Johnson

Tina Turner exploded onto the stage, her legs wicked with rhythm, her haystacked mane looking as if it could ignite from the energy. For an hour and a half she shimmied, strutted and slithered her way into the hearts and libidos of 5,000 Newfoundlanders who packed a St. John’s hockey arena last week for the first concert of her North American tour. The sexiest woman in pop music arrived onstage in white buckskin pants, changed halfway through her show from an ostrich-feathered gown into a loin cloth and halter top layered with diaphanous chain-mail and exited in a black leather mini-dress slit past the hip. But it was her singing voice —the darkening sound of friction between soul and flesh—that drew the crowd to the stage. At the age of 46, Tina Turner has never been hotter. As she is fond of saying to her audiences, “They ask me when am I going to slow down, and I tell them I’m just getting started.”

After nearly three decades in show business, Turner has emerged as America’s reincarnated queen of rock ’n’ roll. With the runaway success of her comeback album, Private Dancer, which has spawned four hit singles, earned three Grammies and sold eight million copies during the past year, Turner’s unusual 10-day sojourn in Newfoundland had all the impact of a royal visit. Exhausted after a three-month European tour, she chose St. John’s as a quiet place to try out a new show before taking it to 86 cities across North America, including 11 in Canada. At the same time, she is winning critical raves for her starring screen role with Mel Gibson in the science-fiction thriller Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. And the release next spring of her biography, by Rolling Stone magazine writer Kurt Loder, which includes a graphic account of her 14-year stint as the battered wife of band leader Ike Turner, promises to be a major publishing event. To help prepare the book she had to overcome a distaste for discussing her past. “I drank a lot of wine,” she said, “but I did it.”

There is a storybook quality to Turner’s life, and her ability to act out her songs in video vignettes helped propel her to stardom. Now she has gone a step further by dovetailing her film performance with her musical resurgence. In fact, she hired Thunderdome’s costume supervisor, Jenni Bolton, to help tailor her image on the tour. The chain-

mail that she wears onstage is a no-frills version of the 70-lb. suit that she wears in the film. And Thunderdome’s bold anthem, We Don’t Need Another Hero, is already rising on the pop charts. Turner is infinitely sweeter as a singer

than as the cruel-lipped Aunt Entity in Thunderdome, but in both roles she is an undeniably commanding force.

Interviewed last week in her St. John’s dressing room, the five-foot, four-inch Turner, wrapped in a blue terry-towel, talked about the kind of star she would like to become. Said

Turner: “I want to do really heroic woman things. I’d like to do a female version of Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo.’’ Recently, she shocked Hollywood by repeatedly turning down an offer to star in director Steven Spielberg’s film The Colour Pur-

pie, based on Alice Walker’s novel about a poor black woman growing up as a victim of brutality. Said Turner: “Black people can do better than that. I’ve lived that life with my husband. I’ve lived down south in the cotton fields. I don’t want to do anything I’ve done.”

The past that Turner is determined to

escape began in the tiny town of Nutbush, Tenn. She was born Anna Mae Bullock and grew up picking cotton with her sister, her Baptist sharecropper father and her half-Cherokee mother. Her parents separated when she was a teenager, and at 16 she and her sister joined their mother in St. Louis, where she saw her first big-city band, Ike Turner and His Kings of Rhythm. One night she grabbed the microphone and unleashed the instrument that her biographer would later describe as “a voice that

could fuse polyester at 50 paces.” During the late 1960s Ike and Tina Turner became white America’s favorite black soul revue. Buoyed by the British success in 1966 of Tina’s River Deep —Mountain High, the two toured with The Rolling Stones. And in 1975 her frenetic stage presence gained broad ex-

posure with her appearance as the Acid Queen in Ken Russell’s film Tommy. But as Tina’s star rose, Ike became an increasingly brutal boss. “I was a little slave girl,” she recalled. “He would beat me so.” One night during a tour in 1976 Tina struck back for the first time, then walked out with just 36 cents and a handbag to her name. Later, she divorced Ike without asking for any money or property, but was saddled with thousands of dollars in damages from the cancelled tour. Valiantly, she re-

turned to the stage with her own Las Vegas revue. Said Turner: “You get a little bit of everything with me — laughter, sex, sadness and then there’s energy.”

Turner’s transformation from supper club singer to rock superstar was guided by Roger Davies, the Australian manag-

er who took over her career in 1982. Two years ago Davies teamed her with members of the British electro-funk band Heaven 17 to record AÍ Green’s soul classic Let ’s Stay Together. It became a major hit in Britain, her U.S. record label gave her $150,000 and she had two weeks to come up with an album. Frantically, Davies solicited songs from various writers, and despite that potluck approach Private Dancer proved to be a cohesive and powerful package. Such disparate songs as What’s Love Got to Do With It? and Better Be Good to Me jelled to form a fresh image for Turner as a wise survivor of the sexual wars. Said John Martin, programming director of the MuchMusic rock video network: “Her success corresponds with a new way of looking at sexy, self-assured women. She’s doing it on her own and she’s a heroine because of that.”

Just as Turner hopes to steer her movie career toward machine-gun heroism, she is anxious to push her music to the front lines of rock ’n’ roll. She relishes her recent duets with such superstars as Mick Jagger and David Bowie, realizing that she is the only female rocker who shares their charmed circle. Declared Turner: “When you’re talking about the guys who can pack those football stadiums, you’re talking about the men that the girls love. So it’s like breaking the rules for me to get a chance to be with them.”

Despite her “tough mama” image, the private Turner appears to be considerably less aggressive than the public one. Practising Buddhism for the past 10 years, she has developed a remarkable talent for focusing her physical energies. Said Thunderdome director George Miller: “I’ve never seen anybody who could be on the one hand so energetic and on the other so still.” Turner herself claims that her reputation as a “strong, scary woman” is misleading. Success has allowed her to pay off about $500,000 in debts and to support seven family members, including two of her children and two of Ike’s. Living in a relatively modest home in a Los Angeles suburb, she remains romantically unattached. Said Turner: “I haven’t really had time to find anybody.”

During the past two weeks in St. John’s, Turner passed up a deluge of social invitations for everything from cod-jigging to helicopter rides. Her sole priority was to prepare the show that would put her in league with the Jaggers and the Bowies of the world. Unlike her heroes, Turner does not write her songs, but she interprets them in a way that makes them her own. In one of them, I Might Have Been Queen, she sings: “I remember the girl in the fields with no name.” Finally, proving herself an intrepid survivor, Tina Turner has become a name that no one will

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER

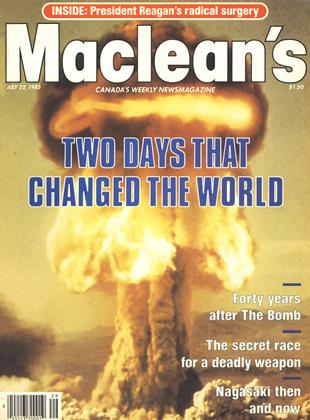

COVERThe dawn of the nuclear age

July 1985 -

COVER

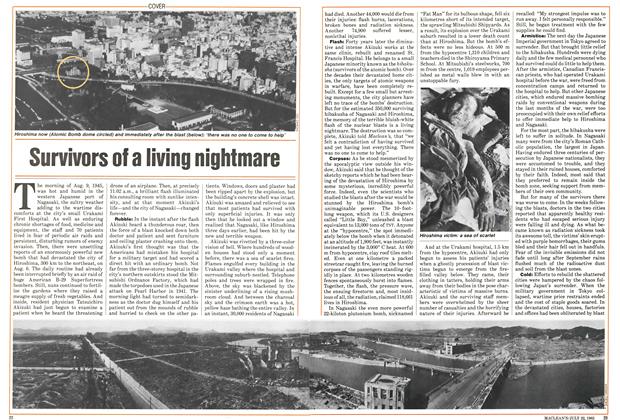

COVERSurvivors of a living nightmare

July 1985 By JARED MITCHELL -

CANADA

CANADARays of hope for an unpopular airport

July 1985 By Bruce Wallace -

COVER

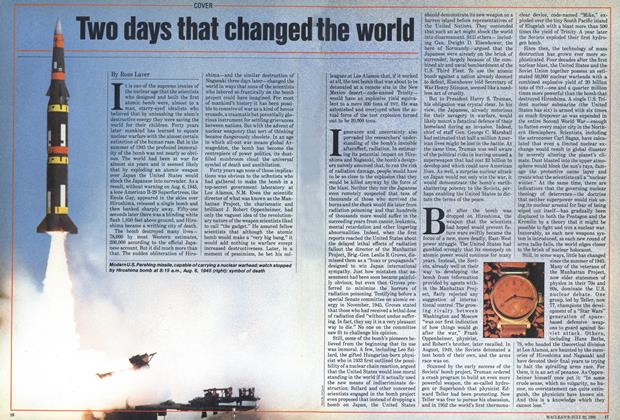

COVERTwo days that changed the world

July 1985 By Ross Laver -

CANADA

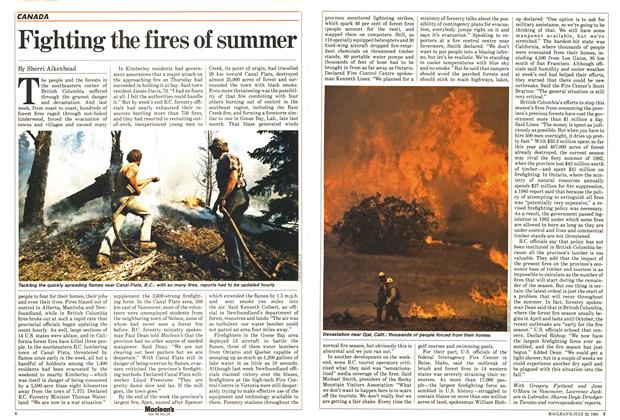

CANADAFighting the fires of summer

July 1985 -

COLUMN

COLUMNThe preoccupation with tears

July 1985 By Charles Gordon